In the lead up to our Open Studio Night on Tuesday 10th October our resident artists caught up to find out a little more about each other and talk artistic practice and influences.

Bruno Booth: So, Emma, can you tell me a little about how your personal history shapes your practice?

Emma Lashmar: My story begins in Perth, and the contrast between suburban sprawl and the rural regions beyond has always played a role in my work. Here we’re poised between desert and ocean, and the sense of isolation is as particular to this place as the light. I grew up with the regular rhythm of school in the city, and holidays in the forests and coastline of the South West. My dad was a sheep farmer turned abalone diver, and so these threads of primary industry and reliance on the land and sea for sustenance have remained vital. I suppose there’s still a part of my practice that’s just a kid sitting in the sand, mucking about with collected flotsam and jetsam. It’s a good place to begin. So with this realisation that materiality is a strong motivator for me, and having discovered a kindling passion for hot glass through visual arts studies at Curtin, I transferred over to Monash University’s glass major program in 2003. That shift was seismic, but Melbourne quickly became home. It’s still somewhat strange to be back in the west for more than a summer holiday!

EL: I could ask you a similar question, Bruno…what’s the origin story of your art-making?

BB: I guess it began with my father and grandfather both being engineers…they were always building things and tinkering with machinery. Watching them work, and helping them with their projects, sort of imbued in me a passion to build things. However, my dad always told me to work with my head, not my hands so I tried that and went to uni. I studied a variety of sciences mainly ecological and environmental and I was into learning about all these crazy systems and how a change in one part changes everything else. However, I wasn’t really happy or particularly good at being a scientist so after a few years I quit and sort of drifted. I played a lot of music and got into that whole scene in Freo and had a great time without really having too much to show for it. After a bit of travelling I came back to Perth and studied Graphic Design at TAFE as I’d always loved drawing but never had any training after high school. The course was really good and I learned a lot of techniques that I employ in my practice but I discovered that I didn’t want to work sitting behind a computer all day (thanks Dad). So I started painting. I painted a bunch of murals around the city, did a few group shows and haven’t looked back and that was about four years ago. In fact it’s only in the last year that I’ve really considered myself an artist and started to focus on developing ideas that will be able to sustain a practice.

BB: I’ve spent a little bit of time in your studio and I’ve noticed that you employ what seems to me to be almost opposing materials can you tell me a bit about that?

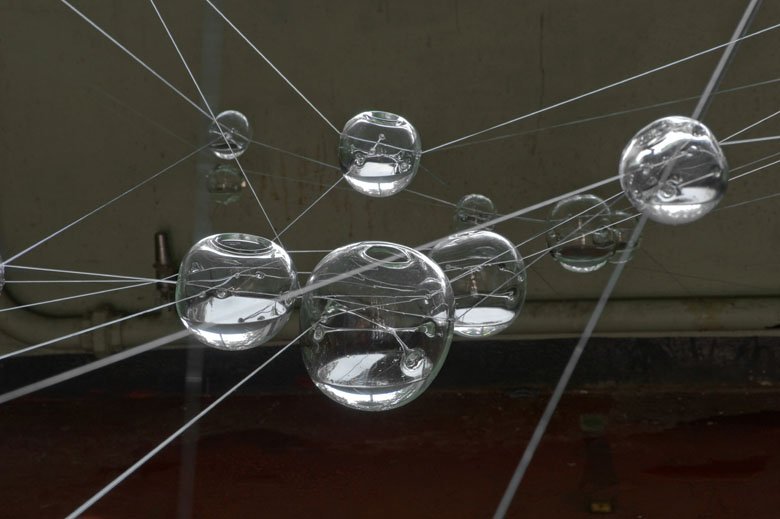

EL: Hot glass has this mesmerising quality, and the process of handling it is as much about the embodied awareness of the maker in process as it is about the design and execution of technique. It requires a physicality akin to performance, as shaping this molten material is all about timing, balance, centring and control. There are so many metaphorical balls to keep in the air, that there’s little time for conscious thought…it requires you to tap into body memory, and work intuitively. Because it is so highly technical, it’s hard to reach and then maintain proficiency without regular practice. So when I do manage to get time in a glass studio, I prefer to play at testing the limits of the material and be content with the imperfections. I don’t need these forms to be flawless, the unintentional marks preserved in the skin of the glass vessel speak to the process of making as a conversation between material and maker… an event in time. I enjoy the aesthetic quirks of the handmade, despite also being compelled to make large groupings of multiples in my work. But for this project, glass could only play a small role. I needed a medium that spoke to more primitive human need. Before the functional vessel emerged, people sought the warmth and protection that clothing and shelter provides. Felt speaks to the fulfilment of these most basic requirements, allowing space and time for higher human consciousness to develop.

EL: Materially speaking, your practice is predominantly painting based, but I’m interested to hear more about the construction of your uniquely shaped canvases. How does craftsmanship play a role in your work?

BB: I think because I’m building the supports for my paintings and the shapes are irregular that craftsmanship does play a role. I try and make sure that the wood I’m using is solid, my tools are sharp and I’ve got everything I need to hand. This allows me to be a bit more spontaneous with the design of the frame. Most of my paintings are loosely planned out on the computer. I then use this image as a reference and draw the shape free hand onto the wood. I then cut out the shape with a jig saw or router, cut out a copy and then glue and clamp these together with a cavity

in-between. Next I trace around the shape onto some canvas, cut out and stretch (with a lot of patience) over the frame.

EL: I feel like another way in which our projects overlap is a desire to delve further into subjective human experiences that are often disregarded on the whole. Can you tell me more about what you’ve unearthed in your current research?

BB: Firstly, up until PICA I’ve tried to keep a distance between certain parts of my life and my art practice. Namely, I didn’t want to capitalise on my disability in order to gain recognition for my work. I know that seems like a weird thing to say but I was always scared of being seen asking for help or asking for hand outs. But now I’ve come to a point where I feel I have more to say than can be expressed simply through nice aesthetics and some flashy finishes. My project has a working title of “Don’t know where to look” and I think it’s about two things. Firstly I’m researching the idea that people who identify as disabled or who are identified by society as disabled are denied this sort of personhood which can only be achieved as a function of their economic productivity. The second idea has to do with the way disabilities are still a taboo subject despite the fact that Australia, like most countries in the West, has an ageing population, an ever growing gap between rich and poor and a society with an increasingly sedentary lifestyle. All of which will lead to an explosion in the number of people classed as disabled in the next 50 years. What I’m grappling with now is how best to represent my research. I’m not a scientist (any more) so I don’t want to be meticulous and literal but at the same time I don’t want to be to esoteric and let the work drift away from the theme.

BB: It was great when you talked me through the felting process the other day and learning about your history with hot glass but we didn’t really touch on your motivations, can you tell me a bit about your ideas behind the work?

EL: The installation work I’m developing was dredged from my subconscious in this kind of psychological purgatory of my daughter’s infancy. At that time, it felt like my critical and conceptual faculties evaporated in a haze of sleep deprivation and hormonal shifts. Like a convalescent recovering from a tropical illness, I found my sense of self slipping through my fingers. It’s not the universal experience of new motherhood, but it was mine. It took all my resources of energy and faculty just to function. But it turns out that this fairly dramatic shift in perspective clarified some questions I’m keen to explore further now that I’ve reconnected with my arts practice. My current research is questioning the ways in which we each develop a personal ethics of care and responsibility to others, to self, to our surroundings. Family life is a delicate balance, both an ecosystem and an economy of sorts, and often just fulfilling the most basic human needs of all parties is a challenge. Food, sleep, hygiene, shelter and communication requirements shape each day, and time passes strangely, without anything discernibly productive getting done. Ultimately through this work I hope to continue evolving the conversation about the ethics of care. I suppose I’m not convinced that our output-oriented society grants enough importance to these roles, or enough respect for the presence and agency we each have in the lives of those around us.

Join the artists for our Open Studio Night to hear more about their practices!